|

|

|

|

|

|

Biological Soil Crusts (BSC): Wlotzkasbaken

Introduction |

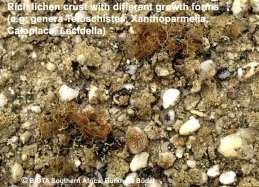

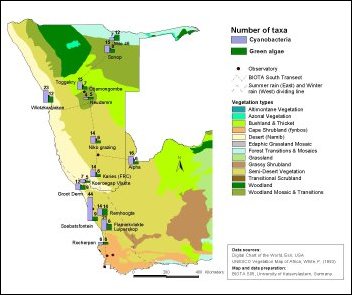

Biological Soil Crusts (BSC) occur in all biomes along the BIOTA-South transect except for the Fynbos. They can be classified into different types depending on the developmental time and the organism composition: three developmental stages of cyanobacterial crusts, mostly associated with green algae (ranging from initial to well developed crusts), lichen crusts (differentiated in cyanolichen and green algal lichen crusts), bryophyte and liverworth crusts, and the hypolithic crust type (community of photosynthetic organisms existing on sides and underneath translucent stones, e.g. quartz) occurring specifically in quartz gravel pavements (e.g. Knersvlakte - observatories Flaminkvlakte and Luiperskop, Namib Desert - observatory Wlotzkasbaken) but also underneath single quartz rocks of different sizes in other regions and biomes (e.g. observatory Ovitoto). Driving forces of such spatial variability of BSC types are climatic, topographic, pedogenetic and land use differences (as in observatory pairs such as Narais and Duruchaus) in different biomes along the transect. |

Dominant Crust Type |

rich hypolithic crust (quartz pebbles) and rich lichen crust |

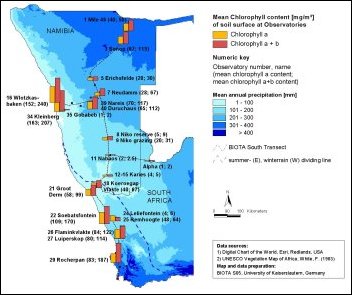

Biological Soil Crust Biomass (chlorophyll) |

very high |

BSC Biomass ranking (from BSC chlorophyll a+b values [mg/m2] )very low <= 10low = 11 to 50medium = 51 to 100high = 101 to 200very high > 200 |

|

Main green algae genera |

|

TrebouxiaChlorellaChlorosarcinopsisDiplosphaeraMyrmeciaStichococcusTotal Taxa No.: 12 |

Implementation of molecular identification techniques - Cyanobacteria |

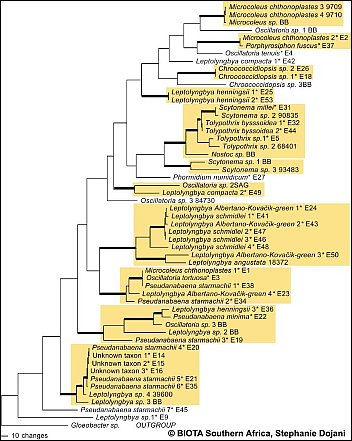

Fig.A: Preliminary results of sequence data is shown in 1 of 6 most parsimonious trees based on 16S rDNA sequences. Asterisks indicate taxa found along the BIOTA South transect.(Please click on map) Fig.A: Preliminary results of sequence data is shown in 1 of 6 most parsimonious trees based on 16S rDNA sequences. Asterisks indicate taxa found along the BIOTA South transect.(Please click on map)

|

The polyphasic approach (morphology and sequence data) is expected to give reliable results in detection of taxa diversity of cyanobacteria. However preliminary results of the molecular analysis of selected cyanobacteria strains (1 of 6 most parsimonious trees based on 16S rDNA sequences) indicate that most of the investigated genera (/Leptolyngbya, Pseudanabaena, Scytonema, Microcoleus/) are polyphyletic. These results are in concordance with findings e.g. by Casamatta et al. 2005. In a second approach, the more variable intertranscribed spacer (ITS) was amplified, which is expected to provide further information on species level.  Casamatta, D.A, Johansen, J.R., Vis, M.L., Broadwater, S.T., 2005, Casamatta, D.A, Johansen, J.R., Vis, M.L., Broadwater, S.T., 2005, Molecular and morphological characterization of ten polar and Molecular and morphological characterization of ten polar and near-polar strains within the oscillatoriales (cyanobacteria) near-polar strains within the oscillatoriales (cyanobacteria) J. Phycol. 41, 421-438. J. Phycol. 41, 421-438.

|

Implementation of molecular identification techniques - Green algae |

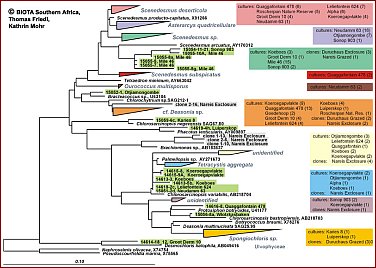

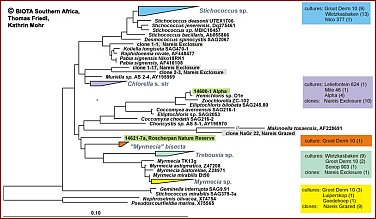

Regarding the algae in BSCs, a large fraction of the algal community appears to be non-culturable, but contributes considerably to the crust biodiversity. Recent studies demonstrate that the true taxonomic affiliations of microscopic desert green algae can only be established reliably with the aid of DNA sequence data, particularly 18S rDNA data. Thus molecuar techniques are required to complement the cultural approach in order to achieve a more reliable assessment of the biodiversity actually present in BSCs. SSU rRNA gene cloning and sequencing is the best established technique for assessing biodiversity from environmental samples with molecular techniques. A more rapid and easy to use technique is DGGE which in combination with cloning/sequences has been found a very useful method to investigate biodiversity of microalgae in and on rocks.Maximum likelihood phylogenies demonstrating the high phylogenetic diversity of green algae obtained from Biological Crusts of 16 different sampling sites in Southern Africa.A total of 279 green algal sequences were obtained from cultures (204) and clone banks (75). They are distributed on many independent lineages and clades comprising the green algal classes Chlorophyceae (Fig. B; 206 sequences) and Trebouxiophyceae (Fig. C; 73 sequences). Colour-coding is used to show the various origins of the groups of green algae. The origin of strains/clones is given in boxes with the number of studied strains/clones per locality. So far, in most cases only a rough genus assigment is possible and several yet unidentified lineages/clades may represent new genera and/or species. Green algae from the "cf. Deasonia", "Scenedesmus deserticola" clades and from a still unidentified chlorophyceaen clade are among the most frequently occuring algal species. There is a general trend with carotenoid-accumulating members of the Chlorophyceae being more abundant than non-carotenoid accumulating Trebouxiophyceae.The phylogenies were obtained from the ARB SSU rDNA sequence database in which partial sequences (350-800 nts in length) from Biological Crust Green Algae were compared with corresponding full-length green algal sequences public databases and unpublished sources using a 50% position conservation filter. Groups of sequences with similarities among each other of 99% and above were collapsed into one triangle. Scale, 10% estimated genetic difference. |

Fig. B: green algal sequences for class Chlorophyceae (206 sequences) (Please click on map) Fig. B: green algal sequences for class Chlorophyceae (206 sequences) (Please click on map)

|

Fig.C: green algal sequences for class Trebouxiophyceae (73 sequences) (Please click on map) Fig.C: green algal sequences for class Trebouxiophyceae (73 sequences) (Please click on map)

|

Related Map(s) |

|

Please click on map(s) Please click on map(s)

|

Functional types of lichen vegetation as the basis for biodiversity and productivity in the Fog Zone of the Central Namib:Significance of microclimatic control as the result of ocean-inland interaction |

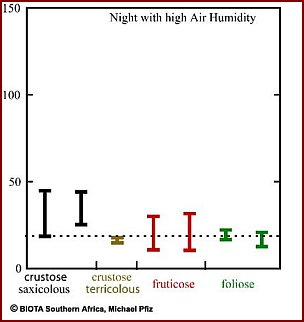

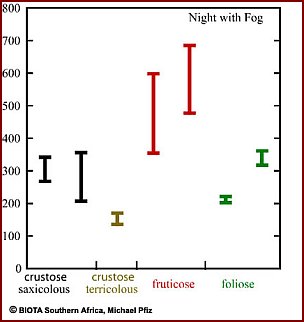

Analysis of the lichen diversity in the Namib Desert resulted in a total of 24 identified species, common genera beeing: Caloplaca, Diploschistes, Lecidella, Ramalina, Teloschistes and Xanthoparmelia. It was shown that different water resources available in the Namib Desert result in functional diversity of lichens: during nights with high air humidity (Fig. 1) particularly crustose saxicolous lichens acquire enough water to enable photosynthesis. At nights with fog (Fig. 2), foliose and fruticose lichen thalli store most water, explaning their high abundance in coastal areas. Crustous terricolous lichens show lowest hydration, presumably due to water storage in the substrate. They occupy the broadest range of environmental conditions.Besides ecophysiology, singular weather events have a strong impact on lichen vegetation: during a thunder storm in April 2003, about 2000 tons of lichen biomass were displaced (mainly Teloschistes capensis, Ramalina spec. and Xanthoparmelia walteri), with 1000 tons blown into the ocean. A further rain event in the central Namib in April 2006 mainly displaced fragments of Xanthoparmelia walteri near the coast, but affected populations of fruticose lichens further inland as well. Preliminary results suggest also an adjustment of the competition between crustose lichens and higher vegetation. As these exceptional events were unforeseen, these investigations extended the submitted time frame for BIOTA Phase II.     From left to right: Fig. 1 and 2: Utilization of different water resources by functional lichen types (gravimetric determination). From left to right: Fig. 1 and 2: Utilization of different water resources by functional lichen types (gravimetric determination). Please click on figure Please click on figure

|

|

|

|